Mega ADAS Test 2026: Safari vs Victoris vs Innova Hycross vs XEV 9S vs Creta N Line vs Carens Clavis EV

India’s top six carmakers go head-to-head in the third edition of our Mega ADAS Test, revealing which driver-assistance systems truly work on our roads.

By Shivank Bhatt

Two years ago, we conducted our very first Mega ADAS (Advanced Driver Assistance Systems) comparison test. Back then, the Honda City and the Mahindra XUV700 were the only two mainstream cars on sale in India to offer ADAS. In 2023, driver-assistance tech was largely seen as a bragging-rights gimmick rather than something truly essential – especially given our less-than-perfect road infrastructure and utterly chaotic traffic conditions.

Truth be told, we didn’t expect ADAS to boom in India – certainly not at the pace it has. And yet, here we are in 2026, with ADAS rapidly becoming mainstream. Today, almost every major carmaker in the country offers some form of driver assistance technology across its latest models. But the biggest ADAS headline in recent times has to be Maruti Suzuki entering the game. With the introduction of ADAS on the Victoris, India’s largest – and arguably most loved – carmaker has officially joined the driver-assistance revolution.

With Maruti Suzuki now in the mix, ADAS is available across the portfolios of India’s top six car manufacturers. The driver-assistance market is getting serious, and the list of ADAS-equipped cars is only set to grow further as we step into the new year.

That said, having ADAS on a brochure and having ADAS that actually works, especially on Indian roads, are two very different things. Every manufacturer worth its salt claims its system is the safest, smartest, and most advanced. But marketing promises only go so far – the real truth comes out only when the rubber meets the road.

Which is why we’re back with the third edition of our Mega ADAS Test. This is our most comprehensive driver-assistance comparison yet, where we evaluate ADAS systems from India’s top six carmakers – Maruti Suzuki, Mahindra, Tata, Hyundai, Toyota and Kia – under identical, real-world conditions.

Automatic Emergency Braking (AEB) Test Explained: Real-World Results

All of the AEB systems in the six contenders rely on sensor fusion, meaning they incorporate a front-facing wide-angle camera for object recognition, and a radar sensor – usually mounted on the front bumper – to calculate distance, speed and time-to-collision.

The camera identifies what the object is – a vehicle, pedestrian, cyclist or motorcyclist – while the radar determines how quickly the car is closing in. When the system detects no corrective driver input, AEB steps in and automatically applies the brakes.

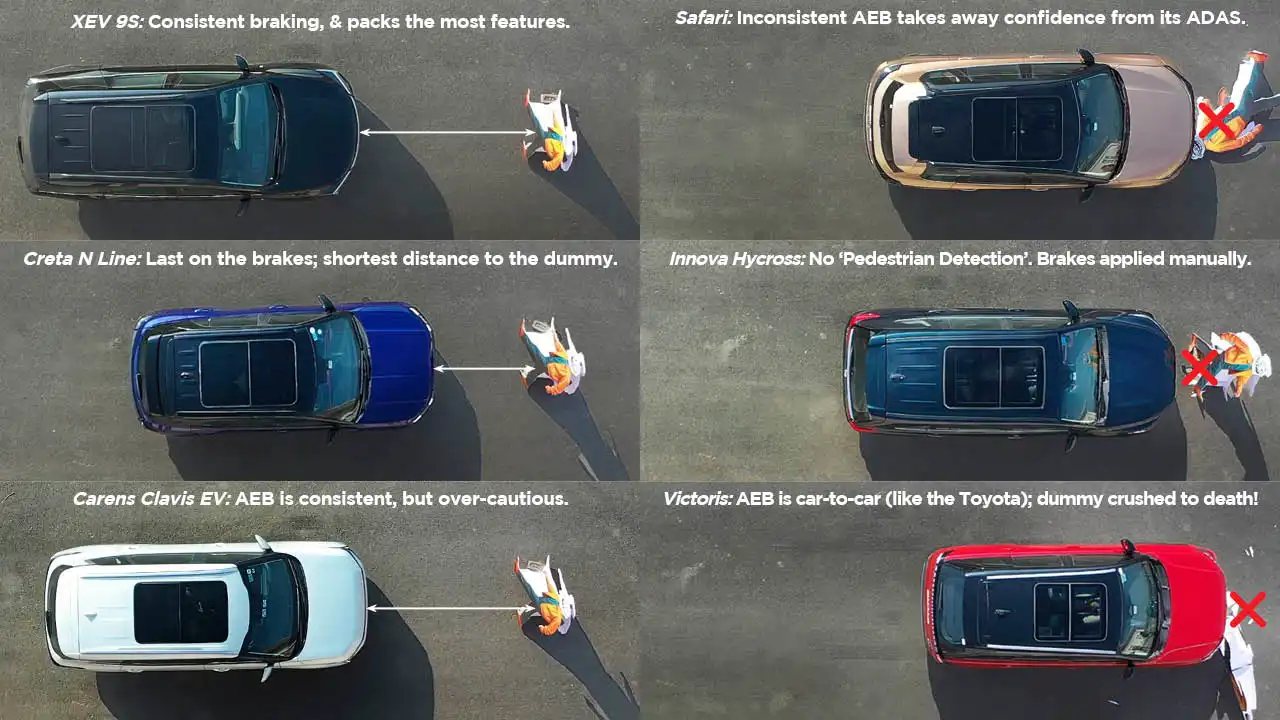

Mahindra XEV 9S AEB Performance: Class-Leading Detection and Braking

The Mahindra performed remarkably in this test. Pedestrian detection and automatic braking were consistent in all three runs – both during the day and at night. The braking was progressive and confident; there was minimal nose-dive, and the ABS didn’t get into overdrive when AEB slammed the brakes – something that we had experienced with the XUV700 in our previous tests. Also, Mahindra’s AEB offers a longer brake hold after the vehicle comes to a stop, preventing a quick roll-forward.

Compared to the others here, the XEV 9S has more tricks up its sleeve – beyond detecting vehicles, pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists, its AEB can also identify general objects, including barricades and a cow – a feature uniquely relevant to Indian roads. That said, the cow has to be of a certain spec – at least 1m in height & 0.5m in width. Among other unique features, Mahindra’s AEB gets ‘Automatic Emergency Steering’. It’s basically an evasive manoeuvre, where the system can steer or swerve around a pedestrian to avoid a collision. However, like with everything in ADAS, conditions always apply. This means that for AES to function, there should be enough empty space for the car to complete the move.

Kia Carens Clavis EV AEB Review: Consistent but Over-Cautious

The Carens Clavis EV uses the same ADAS as the Kia Seltos (previous-gen) – the winner of our previous ADAS test – so expectations were naturally high. While detection consistency was excellent, braking behaviour was noticeably aggressive. The weight transfer was quite prominent, and it didn’t brake with the same sure-footedness as the Mahindra. Unlike the Mahindra, which gives you time to process what-just-happened, the Kia released the brakes after just two seconds.

There’s no doubt that this system prioritises safety; albeit it’s a little too cautious, as it hit the brakes earlier than expected and brought the car to a stop much earlier. This suggests that in real-world driving conditions, this system is likely to be the most trigger-happy, despite the AEB being set to Late. In the dark, the Kia was again consistent with its AEB performance, although the headlamp throw wasn’t as strong as the Mahindra's. This may affect its performance in less-than-ideal scenarios.

Hyundai Creta N Line AEB Test: Sharp Calibration, Accurate Stops

The Creta was the only manual transmission car in this test, making for an interesting AEB prospect. Now, despite the complexity of integrating ADAS with a manual gearbox, Hyundai’s calibration was quite impressive. The system detected the dummy at the very last moment, yet braked accurately, registering the shortest distance to the dummy after coming to a halt.

The braking felt much less jerky than the Kia's, though in terms of consistency, it was just as good, if not better. At night, the Creta’s AEB performed flawlessly again, stopping at virtually the same spot during all three attempts.

Tata Safari AEB Performance: A Mixed (& Inconsistent) Bag

Tata’s ADAS showed mixed results. During daytime tests, the system detected the pedestrian but failed to stop in time, resulting in a collision with the dummy two out of three times. It did stop in the third attempt, but not as convincingly as the others. So, if you talk about consistency, the Safari scored poorly. The surprising bit, though, was that its sensors detected the dummy on all occasions but failed to stop the vehicle.

Unexpectedly, the Safari’s AEB worked flawlessly at night! It stopped with the same consistency as the other contenders, halting at exactly the same spot in all three attempts. We aren’t quite sure what changed or how the system suddenly improved its performance. All we can say is that our spare dummy – the Knight – was quite happy to not meet the same fate as the Troll.

Toyota Innova Hycross AEB Limitations: Car-to-Car Only System

The Innova Hycross’ system is primarily designed for car-to-car collision prevention, meaning it’s not designed to detect pedestrians, motorcyclists, or cyclists. Regardless, we decided to test its AEB system with our dummy placed bang in the middle of the road.

As expected, the Toyota didn’t detect the dummy, let alone make the effort to brake. Since our dummy had already been through a lot – courtesy of the Safari – I saved the day by slamming the brakes on all three occasions to avoid hurting, and eventually killing, our dummy.

Maruti Suzuki Victoris ADAS Review: Entry-Level AEB with Key Gaps

This is the most important one, if you ask me – the country’s largest car manufacturer offering ADAS for the first time. Maruti Suzuki has democratised almost all automotive technologies in India, so can it do the same with ADAS in the Victoris? Well, in a way it has, but it’s not without its drawbacks. You see, just like Toyota, the Victoris too doesn’t offer pedestrian detection – its AEB is limited to car-to-car. And just like with Toyota, we couldn’t test the performance of its AEB system.

That said, it didn’t stop us from trying. Again, like the Hycross, the system failed to detect the dummy on all three occasions. In the last attempt, the dummy was crushed to pieces by the Victoris, marking its untimely death. No need to feel bad about it, though – he was a troll, anyway.

AEB Test Verdict and Rankings: Which ADAS System Performs Best?

At the end of the test, one thing was evident – no matter how identical these systems sound on paper, they are not created equal.

All said and done, we have to rank the contenders based on their performance. Mahindra took top spot in the AEB test, setting a clear new benchmark among its rivals.

Hyundai comes in a close second, thanks to its excellent tuning and stopping accuracy. Its sister brand, Kia, completed the podium – it was as good as Hyundai but turned out to be somewhat over-cautious. Tata took fourth place simply because it offers better pedestrian safety than Toyota and Maruti Suzuki. That said, Tata’s system definitely needs refinement, as its current performance wasn’t trustworthy.

Lane Keep Assist, Adaptive Cruise Control & Blind Spot Monitoring Tests

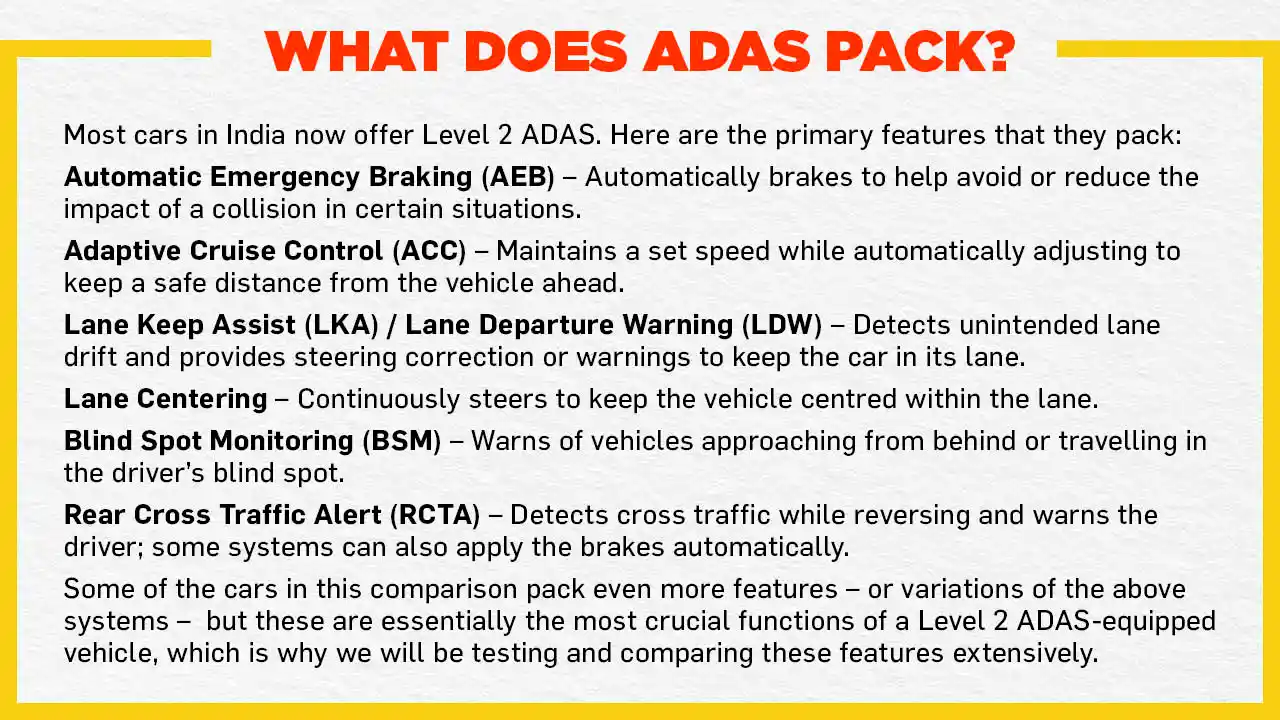

Different carmakers may use different terminologies and abbreviations for Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC), Lane Keep Assist, Blind Spot Monitoring, and Rear Cross Traffic Alert, but the underlying working principles are largely the same.

Typically, ACC systems activate above 30km/h, with adjustable following distances ranging from 25m to 125m. Lane assist, or lane centring functions, usually come into play at around 60km/h. However, as we’ve already seen in the AEB test, similar hardware doesn’t always translate to similar behaviour on the road, and, hence, this second part of the test.

Mahindra XEV 9S ADAS Review: Highway Assist and Semi-Autonomous Features

Starting with the XEV 9S, it once again offers the most exhaustive ADAS feature list in this group. Its adaptive cruise control is paired with Mahindra’s Highway Assist, which enables semi-automated lane changes. When stuck behind a slower vehicle, all you need to do is indicate, and the system checks if the adjacent lane is clear before executing the manoeuvre. When it works, it genuinely feels futuristic.

Lane centring is another strong point. Steering inputs are minimal, and the wheel stays rock-solid. Even on curving highways, it stays centred without fuss. The head-up display is excellent too, clearly showing warnings and blind-spot alerts without taking. your eyes off the road. That said, the ACC can feel a bit aggressive. Braking when a vehicle is detected ahead can be abrupt, and acceleration once the lane clears can be sudden. About 90% of the time, it behaves predictably, but with so many features layered in, the system can feel overcomplicated.

Kia Carens Clavis EV ADAS Performance: Strong Features, Nervous Steering

The Carens has one of the most comprehensive ADAS packages after Mahindra. Its ACC itself works well, particularly its adjustable acceleration settings. Low, normal, and high modes allow you to tailor responses, with normal offering the best balance of urgency and smoothness. Where the Carens falls short is steering behaviour.

Even on straight roads, lane centring makes frequent micro-corrections that are clearly felt through the wheel. Braking during cut-ins or when detecting slower traffic ahead can also be abrupt, unsettling occupants and surprising drivers behind.

Hyundai Creta N Line ADAS Explained: Lane Assist Without ACC

The Creta N Line manual shares much of its ADAS hardware with the Carens, but surprisingly misses out on adaptive cruise control, especially odd given that Honda offers ACC on manual versions of the City and Elevate. You still get Lane Departure Warning, Lane Keep Assist, Blind Spot Detection, and conventional cruise control.

Lane centring activates above 60km/h and is better tuned here than in the Carens Clavis EV – steering corrections are gentler and less intrusive. On highways, the system keeps the car centred confidently and feels natural through curves.

Toyota Innova Hycross ADAS Calibration: The Most Natural ACC Experience

The Hycross didn’t score well in the AEB test as it lacks pedestrian detection. But out on the open road, it tells a very different story. Cutting straight to the chase, this is one of the best-calibrated ADAS systems currently on sale in India. Set adaptive cruise control at highway speeds, and the Hycross reacts calmly and predictably.

There’s no sudden brake slam or aggressive deceleration, unlike several other contenders here. Instead, it lifts off gently and slows down progressively, which inspires confidence almost immediately. Even in sudden-stop or cut-in scenarios, the system responds smoothly without overreacting. Add curve-adaptive cruise control, which reduces speed gradually on long bends, and you get a system that feels natural, intuitive, and trustworthy. Simply put, Toyota’s ADAS feels the most human-like of the lot.

Maruti Suzuki Victoris ADAS on Highways: Predictable but Limited

The Victoris’ ADAS will feel instantly familiar after driving theToyota. The interface, layout, and display logic are clearly shared, and that tech transfer shows in real-world behaviour. On highways and expressways, the Victoris feels extremely predictable. Steering inputs are gradual, with no nervous corrections on straight roads.

Through long, sweeping curves, the system lifts off gently, albeit there is a caveat. Around certain curves, the system can disengage suddenly, which can be unsettling. A standout feature is the presence of large physical buttons near the steering column to disable AEB or lane departure warning – hugely convenient when you don’t want to dive into touchscreen menus.

Tata Safari ADAS Review: Smooth ACC, Weak Lane Assist

The Safari remains a mixed bag. Its adaptive cruise control is well tuned, with smooth, progressive deceleration that feels more natural than Mahindra or Kia. Blind spot detection and rear collision alerts also work reliably. The major issue is lane centring.

Despite having buttons and menu options, the feature wasn’t functional during testing. Lane departure warning worked, but without steering correction, it felt incomplete. Another concern is braking behaviour when overriding ACC–if you accelerate manually and then lift off, the system reapplies brakes abruptly instead of gently waiting for the gap to open.

ADAS Comparison Verdict: Best and Worst Systems on Indian Roads

In the second part of our test, Toyota emerged as the clear winner, with the most natural and least troublesome ADAS calibration. Mahindra finished second, leading the field in innovation but still needing refinement. Kia, Maruti Suzuki, and Hyundai were largely on equal footing. Tata’s ADAS once again left us wanting more, lacking consistency and predictability across both tests.

ADAS at Night and Zero Visibility: Why These Systems Fail

After our previous two Mega ADAS tests, we received multiple requests to evaluate how these systems perform at night. This time around, we made sure to include a dedicated nighttime test.

Interestingly, all the vehicles performed at night exactly as they did in broad daylight – and the Safari, in fact, was even more consistent in the dark. Thanks to strong illumination from their LED headlamps, all vehicles – except the Toyota and Maruti Suzuki – had no trouble detecting the pedestrian and applying the brakes. In short, as long as your headlamps are working properly, AEB should function as expected at night.

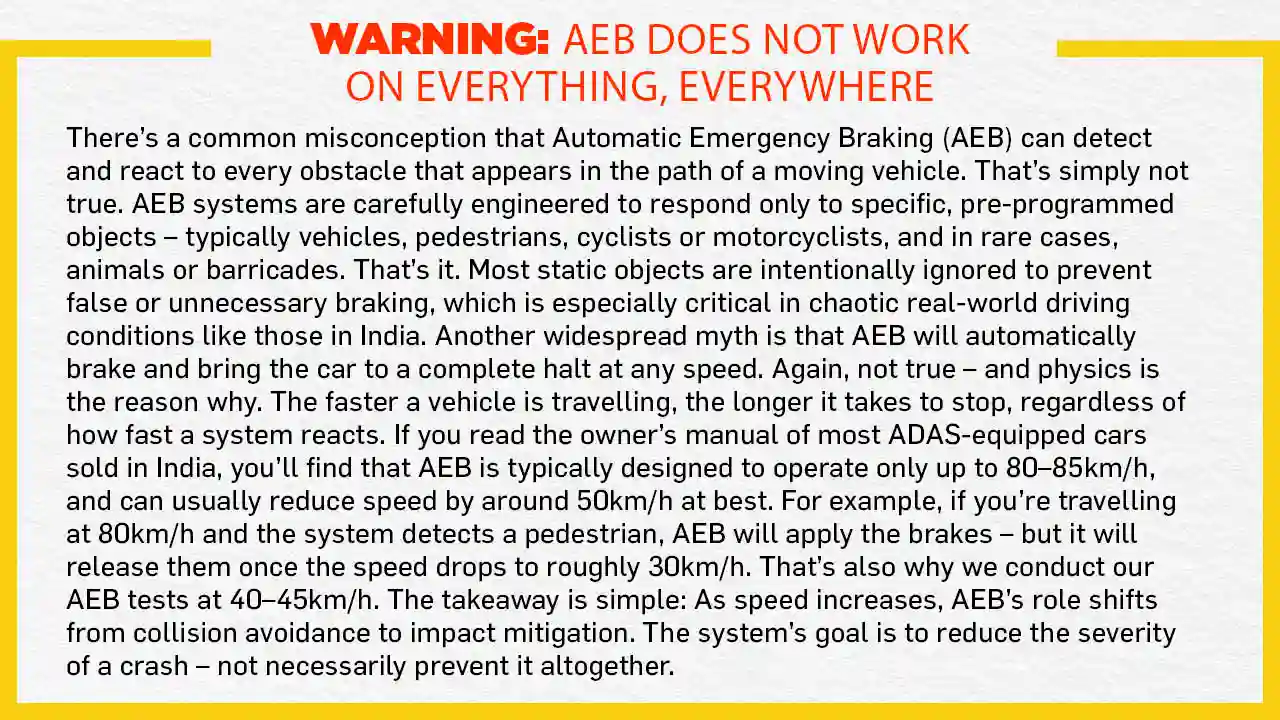

But what happens when visibility drops to zero? To simulate this, we turned off the headlamps – and even the DRLs – on all the vehicles and repeated the same tests at identical speeds. The result was unanimous: none of the systems detected the pedestrian, let alone applied the brakes. So why did ADAS fail across the board, even though all these cars use radar technology?

The answer lies in how AEB systems are designed. While radars are excellent at detecting large metallic objects uch vehicles, they are less effective at classifying pedestrians. That task is primarily handled by the front-facing camera. All the AEB systems tested here use a camera–radar fusion setup. The camera identifies and classifies the object, while the radar calculates distance and time-to-collision. For AEB to activate, both inputs must work together – not independently.

When the camera goes blind because of insufficient illumination, the system is left with only radar data. With incomplete information, it cannot make a confident braking decision – and therefore chooses not to intervene. On the flip side, this is exactly why radar-based systems perform well in detecting moving vehicles (large metallic objects, remember?) in tricky weather (fog, rain, etc.). This is something that’s clearly evident when you use the adaptive cruise control (ACC) feature in dark or low-visibility driving conditions