Remembering Sanjay 'Hardy' Sharma, Hard Nut to Crack

For three decades, Sanjay 'Hardy' Sharma was the backbone of Indian motorsport, mentoring icons at JK Tyre Motorsport. A tough mentor, an even better friend.

By Vinayak Pande

There are, in my experience, two ways of knowing someone. Your own interactions with them and hearing what others have to say about them. After the shock to the news of his demise had subsided, I thought about how I knew Hardy, a.k.a. Sanjay Sharma.

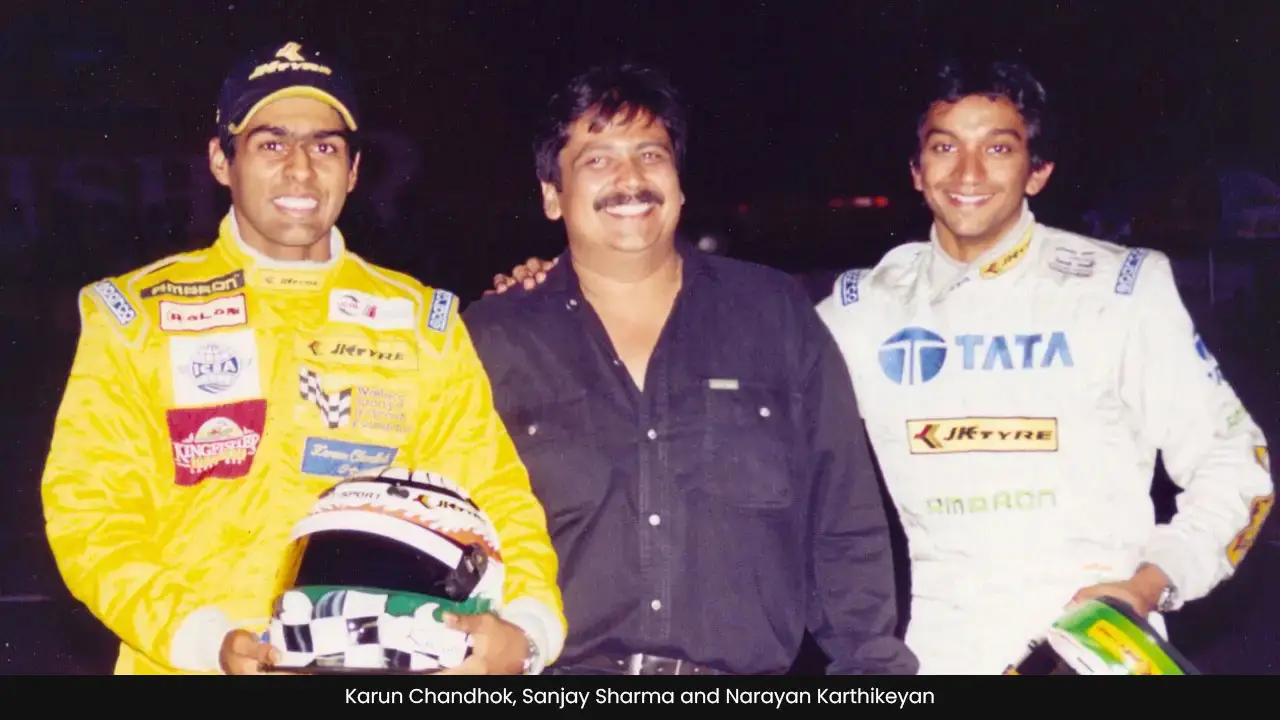

As a journalist, my interactions with him were instrumental in making sense of domestic motorsport in India. Until I started covering domestic motorsport in 2007, I was pretty much unaware of its existence while intensely following global motorsport. I was aware of Narain Karthikeyan’s head-turning successes in Formula 3 that eventually led to his historic Formula 1 debut and of Karun Chandhok trying to follow in his footsteps. However, I had no idea of the ecosystem they came from. Not to mention who – in that ecosystem – was instrumental in discovering and promoting them both.

When I first met him at a round of the National Racing Championship at the Madras Motor Race Track in late 2007, I was struck by how easy it was to get information from Hardy. Among all the people I interviewed he was the only one – to the best of my recollection – to never say that the information he was giving me was ‘off the record,’ being told in confidence or should not be attributed to him.

His candor extended to every other journalist who spoke to him as well. I recall some of my peers being surprised after I told them information that I got from Hardy that they thought was an inside scoop they had acquired through ‘schmoozing.’ He was well known for his openness with anyone who sought information, guidance, or came to him with an idea.

Along with being of help to write a story, Hardy’s openness was a relief to me personally. There was – and probably still is – a prevailing notion of journalists needing to get used to indulging in drinking or partying to get close to a credible source. As a teetotaler, non-smoker and someone who didn’t always mingle easily with people, I never had to step out of my comfort zone while doing my job thanks to Hardy.

As I discovered in September of 2008, Hardy was more than willing to step out of familiar surroundings if it got the job done. While on assignment at the Sachsenring in Germany I heard a voice call out my name from behind me. I turned around and saw Hardy smile and greet me with a “what’s up brother?” It felt like seeing a fish out of water, as I had only associated Hardy with the domestic motorsport scene. As it turned out, he was there to take care of business for domestic Indian motorsport as he made a beeline to the head of Volkswagen Motorsport. Lo and behold, in 2010 the Volkswagen Polo Cup India got underway in association with JK Tyre. Hardy had managed to associate JK Tyre with an automotive giant like the Volkswagen Group.

After that, I was never surprised by any deal that Hardy managed to pull off. While there are many such moments that defined Hardy to me, I ultimately only knew of him rather than know him personally. Those who know him best are some of the most prominent Indian motorsport athletes in history – including the man who credited Hardy with making him India’s first professional rally driver, Hari Singh.

“I first met Hardy in 1992, when I was already the Group N champion,” said the first Indian to win the Asia Zone Rally Championship. “The arrive-and-drive system that Hardy started was revolutionary because it meant I could get paid for the first time. Before that, there was only the option of having to pay to compete in motorsport. Because of that, JK Tyre could field a big team to compete in rallying.”

When asked if there was a memory of Hardy that Singh felt defined him, he recalled one from the early 2000’s when Singh was competing in the Asia Zone Rally Championship. The JK Tyre team was disqualified from the Indonesian round because the homologation papers for the cars’ gearbox had not reached in time.

“The homologation papers were stuck in England because the guy who was supposed to send them was off on a cycling trip,” recalled Singh. “We also had another issue because the chief steward at the event was Nazir Hoosein, who we suspected was already beginning to side with MRF.”

For context, the motorsport rivalry between JK Tyre and MRF went well beyond racetracks and rally stages. It was, and I guess still is, a battle for the control of Indian motorsport itself.

Singh recalled that despite Hardy’s requests to hold the results of the rally and that the papers would eventually reach, Hoosein would not budge.

“Hardy stormed into his office and withdrew the entire team,” said Singh. “But what struck me was that Hardy didn’t allow us to feel upset or sorry for ourselves. His motto was ‘Win or Lose, We Still Booze.’ We would treat a loss the same way as we would treat a victory.”

Another Indian rally legend saw, first hand, that celebrating victory was something Hardy didn’t have a problem with, even if it wasn’t one for JK Tyre. “I was with MRF when I became the first Indian to win the FIA Asia Pacific Rally Championship,” said Gaurav Gill. “Hardy gave me a drive for the JK Tyre rally team after he saw me win an autocross event on my first attempt. And even after I left JK for MRF in 2007, he would still be there for me.” In 2013, Gill found out just how involved Hardy was willing to be in his life even if he was with a rival.

“I was coming back home from China after winning the APRC title and I reached by 1am and saw all the lights were out in the house,” said Gill. “I thought everyone was out somewhere but then I got in and suddenly Hardy appeared with 100 other people and drenched me in a champagne shower. The fact that he was there for such a special moment in my life, despite me not even driving for him, showed how much he genuinely cared for people.”

Hardy was also there for another highlight in Gill’s career, winning the Arjuna Award in 2019. It was the first time a motorsport athlete had been awarded India’s highest sporting honor. “I was only allowed to take four people with me to Rashtrapati Bhavan and I knew Hardy had to be one of them.”

Despite his roots in rallying, Hardy didn’t overlook circuit racing, especially as the popularity of Formula 1 went global. The opportunity was there to put both India on the map, so to speak, but also to take the JK Tyre brand to a global stage. Sponsoring Narain Karthikeyan, as he made his foray into Formula 3, was the starting point as more Indian racers made their presence in junior formula series known. This brand building was something that Karun Chandhok was both witness to and involved in as well. “Something Hardy could do that no one I know in the world of motorsport was he could just implement an idea after thinking it,” said Chandhok. “He literally created the JK Racing brand in 2007 when I went for the GP2 test at Paul Ricard.”

Bridgestone refused to let Chandhok run with JK Tyre branding on his car, which prompted Hardy to make a new company and logo – that was then seen prominently displayed on Chandhok’s car. And it didn’t stop there. “When the Indian Grand Prix was coming, he called me and said ‘boss, I don’t have the money to enter a Formula 1 team, I need a way to have a presence on the grid,’ and that’s how the JK Racing Asia series started,” said Chandhok.

“I told him about the Formula BMW Pacific cars, and that’s how it became the JK Racing Asia Series, even though the tyres were Michelins.” The result was a support series during the inaugural Indian GP with cars built to international standards and a field entirely made up of Indian drivers.

Incidents like these made Chandhok aware of just what a person Hardy was along with another, more personal memory. “I think I was 10 or 11 years old when I first met Hardy during a rally where my father (Vicky Chandhok) was competing for the JK Tyre team and I didn’t have a way to follow the rally,” said Chandhok. “Hardy came along and was with me for the entire event, be it going to the stages or the service park. He taught me how to make egg paranthas by the side of the road.

“He was a real one-off. I learned more from him than anyone on the planet, apart from my family. Especially about brand building, which he did for the Singhanias who trusted him completely.”

That brand loyalty led to what Chandhok said was the only time him and Hardy didn’t see eye-to-eye.

Indian motorsport fans probably remember the 2012 Sidvin Festival of Speed and the buzz of optimism in the air. In the wake of the Indian GP, JK Tyre and rivals MRF agreed to hold their respective racing series on the same weekend. MRF’s technical expertise mated with JK Tyre’s promotional and marketing expertise even had me all giddy when I covered the round at the Buddh International Circuit.

Twenty thirteen was a rude awakening, though. First a tax dispute between Formula One Management and the Indian government brought the curtains down on the Indian GP. Then news came of the bonhomie between MRF and JK Tyre ending and the Festival of Speed being no more. “It was Hardy who wanted out of the agreement, and I did not agree with him at all, but over time, I saw his point of view,” said Chandhok. “Hardy told me that his brand gets compromised if it shared space with others. Above everything else, he took decisions that were best for JK Tyre rather than anyone else or based on idealism.”

Another ‘ism’ that can be attributed to Hardy was pragmatism. Former national karting and racing champion Rayomand Banajee experienced it and remembers the effect it had on him. “I first met Hardy in 2000 in Pune during the JK Tyre National Karting championship,” said Banajee. “I found him to be quite humble, encouraging, helpful and thoughtful, but at the same time Hardy could also tell me what I didn’t like hearing, but needed to hear.”

Banajee recalls when he was in contention for the FISSME National Racing title in 2003 and lost it by a close margin, prompting Banajee to contemplate what could have been. “I was feeling very sorry for myself while talking to Hardy at the end of the race and going through the different scenarios in which I could have won the title,” said Banajee. “Hardy very simply said ‘if aunty had balls, then she would be uncle.’

“It was not demeaning, but it hurt when he said it, however it turned out to be one of the best things anyone has ever said to me.”

Hardy would have an even more transformative effect on Banajee in 2009 when he encouraged the then 28-year-old to move on from racing despite still being a consistent race winner and title contender in karting and single seat racing in India. “It was in the wake of Narain reaching Formula 1, being successful in A1GP and of Karun reaching GP2 and becoming a race winner there,” said Banajee. “I still had ambitions of reaching F1 or a series in Europe at the time, so Hardy’s words did hurt, but it wasn’t empty advice.”

Banajee is now a respected driver coach and a team owner in the National Karting Championship and was responsible for nurturing the careers of young racers including Jehan Daruvala.

Of course, it isn’t just motorsport athletes who can recall moments with Hardy that felt significant to them. I already have added my own perspective as a member of the media, but there are others whose insights into Hardy carry a lot of weight, in my opinion.

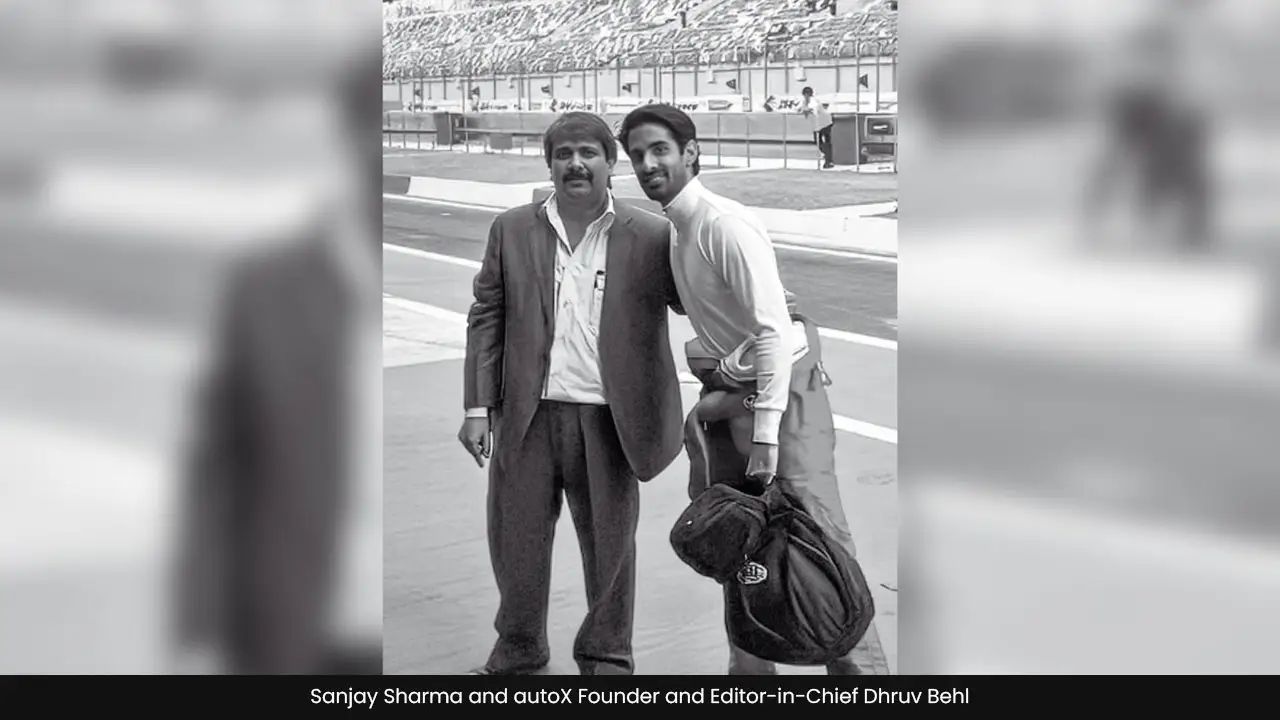

“People called Hardy Mr. Motorsport, but for me he was the godfather of Indian motorsport,” said Dhruv Behl, autoX editor-in-chief. “He was the first person to give me an ad when I started autoXchange, which later became autoX.

“He was larger than life and had a very big heart. Not to mention proper first-hand knowledge of motorsport.”

Hormazd Sorabjee, who was my editor in chief at Autocar India recalls first seeing Hardy as Tutu Dhawan’s co-driver in the Great Desert Himalaya when Sorabjee himself was competing. “There’s a lot one can say about Hardy, but above everything else he knew how to nurture talent,” said Sorabjee. “Narain, Karun, Hari and Gaurav all have Hardy to thank for reaching a high level in international motorsport.”

Sukhwant Basra, the former national sports editor of Hindustan Times had a unique perspective to Indian motorsport on account of being a frequent competitor in two-wheel rallying and rally raid events like the Raid de Himalaya. Naturally he had a lot to say about Hardy considering his experience as an athlete and a prominent member of the national press.

“To be perfectly honest, I initially found Hardy to be quite a pushy guy, but as time went on, I really started to admire the guy,” said Basra. “I used to do a lot of hard stories on motorsport and Hardy was one of the few people who took it in the right spirit. Despite whatever I wrote, Hardy and I stayed friends.

“He genuinely cared about motorsport in India and, as I found out, he didn’t care if JK was involved in it or not. I once tried to needle him by mentioning how MRF was taking journalists to cover the FIA APRC rounds when Gill was competing. He said that it was amazing and that it would be great for Indian motorsport to get good coverage. I realized then that he always put the sport first.

Basra recalls Hardy even supporting motorcycle rally competitors along with all the drivers already being sponsored by JK Tyre. “Getting JK Tyres was a big deal for aspiring rallyists and many times Hardy would even pay their entry fee,” said Basra. “I even recall when he once gave three riders from Chandigarh two lakh rupees to cover their costs of competing in a rally.

“He also had a knack for seeing the big picture and was the ultimate dealmaker in Indian motorsport and a very important figure in it. He was a rare guy, and Indian motorsport will truly appreciate him now that he is gone.”

My former colleague and a fellow motorsport editor – a nice job designation in an already niche field of journalism – Vaishali Dinakaran recalls Hardy being very straight forward and courteous with her despite her professional inexperience during their first meeting.

“I first met Hardy at the Kari Motor Speedway in May 2008,” recalls Dinakaran. “It was a month or so before I was to officially join Autocar India, but the magazine had sent me to cover a round of the Rotax Max Asia Challenge.

“Since I had been deputed to cover an event before actually beginning work, I didn’t even qualify as a cub reporter, but that didn’t seem to matter to Hardy. He treated me with the same courtesy that he extended the more experienced journalists. No question was too silly, controversial or confrontational for him to officially answer – something that never changed.”

Another thing that stands out for Dinakaran is Hardy’s proclivity to “calling a spade a bloody quick shovel.”

“Very early on I had asked him who he considered to be a driver to watch out for,” said Dinakaran. “Of course, he could have named any one of the JK Tyre backed drivers who were doing relatively well in various series around the world, but he didn’t. He named a driver who, though competing in a JK championship, wasn’t one of the more prominent names. It was a useful tip, and of course he was right about the talent the driver possessed, even if he never ‘made it.’

“Over the years I also remember him acknowledging talent within the Indian motorsport fraternity irrespective of who might have been sponsoring said talent. It is a quality that I don’t believe necessarily extends across the board and it goes without saying that any Indian driver who competed in a racing championship abroad owes him an immense debt of gratitude for helping them get there.”

During my conversations with Hardy, he often told me to not be impatient with regards to developments in Indian motorsport. And while that approach didn’t necessarily quell my impatience, Hardy's record of nurturing Indian motorsport talent and its ecosystem speaks for itself.

-1771238312267.webp)